|

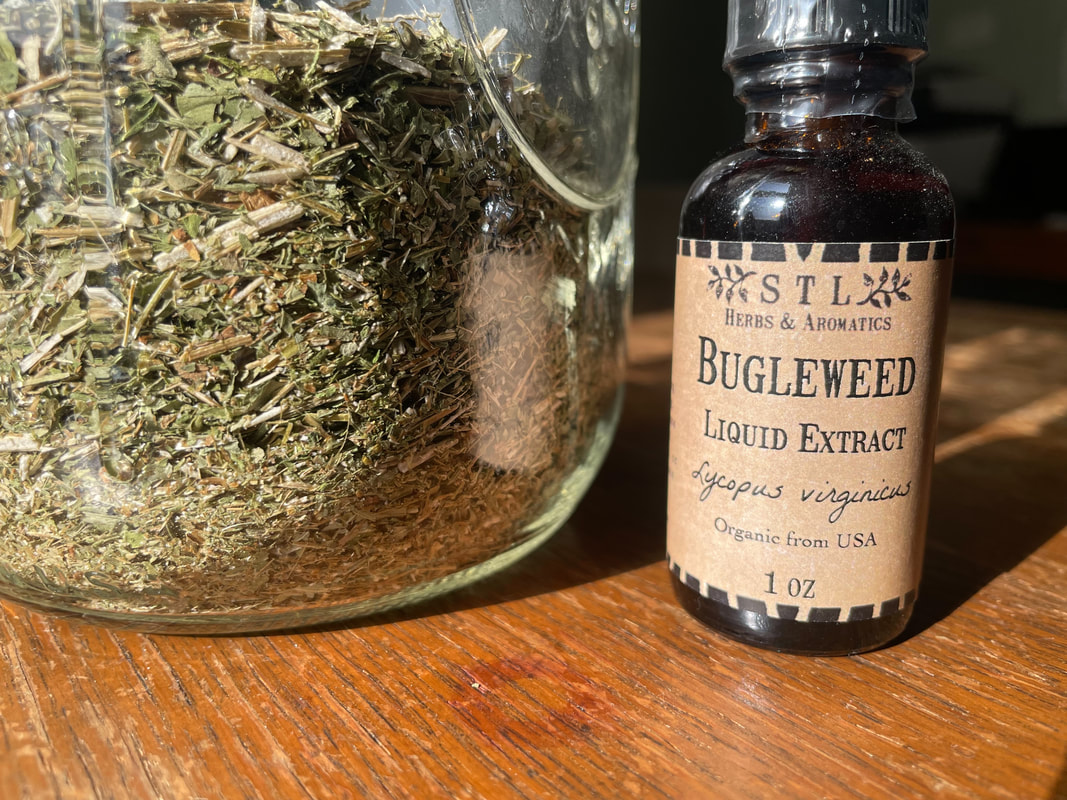

BUGLEWEED Lycopus virginicus Family: Lamiaceae Running on Empty, the Hyper Vigilant Heart The composition of a gray, rainy summer day in Missouri’s flood plain wetlands draws the eye across an array of murky landscapes: from saturated marsh land in remnant river channels, home to bitterns, frogs and muskrats, migratory ducks and shorebirds; to where rivers meander and turn in upon themselves forming self-contained oxbow lakes, habitats for snakes, crayfish, and turtles; to partly submerged rain-soaked trees, sullen and silent, standing in darkened riverside swamps; to the bottomland forests latticed with dripping vines, canopied over by cottonwood trees that rise tall above shrubs of pawpaw, spicebush, and wahoo; to softly-mudded prairie and meadowlands, their colorful floral abundance ghost-like in the gloom; and finally, to the seeps and bubbling springs discharging water onto an already inundated flood plain. The cloudbursts continue: the pace of creeks and streams increases; ponds and lakes overwhelm their edges; and the rivers share their water with the plains. The aroma of water-swollen alluvial soil hangs like a mist over the land, and Missouri’s moisture-loving wetland plants rise from the mud to face the rain. From watery reservoirs came life’s curious. Originally, life was contained underwater. Living billions of years in underwater colonies, the first photosynthetic organisms, cyanobacteria, utilized sunlight for food and released oxygen as waste. Water began to fill with breathable oxygen; bubbling up into the air, oxygen began accumulating in the atmosphere. Over time, the availability of oxygen created opportunity for ever greater diversity of life. It was, however, freshwater photosynthetic green algae that spawned the first ancestors of land plants. When any of their small, wet environments fell dry, the algae, finding itself land locked, struck a bargain to continue to survive. From certain of the soil’s bacteria, algae took genetic instruction in how to cope with the demands of a terrestrial environment. . . and the plant portal from fresh water to land opened. As a transitional ecosystem, the flood plain wetlands can be seen as an evolutionary step directing plant life from fresh water toward higher, drier parts of earth. Its various vegetal characteristics result from a cresting and falling water table that, influenced by weather, geology, soil composition, and ground cover, ultimately determines what the wetland plant life can achieve in the form of overall productivity, diversity, aesthetic appeal, and contribution to life on earth. Comparable to rain forests and coral reefs, flood plain wetlands are considered one of the most important types of ecosystems. A storehouse of nutrients; a place of refuge and fecund home to innumerable species of life, many of which are endangered; and, as part of the main, having a natural impulse to govern flooding, thereby controlling erosion, water supply and water quality, the gifts of flood plain wetlands easily exceed their borders. Its primeval energy and protean nature give this ecosystem a place of prominence in life’s determined progression. Human intervention in its ancient business, in the form of poorly regulated agricultural, urban, industrial, and deforestation practices, makes tenuous the life-giving hand that such wild land ordinarily capably extends. When flooding occurs, the wetlands control excess water through processes of storage and filtration. The profuse vegetation found on healthy flood plain wetlands can trap and slowly release back to land the excess water, preventing soil erosion as well as erosive damage downstream. At the same time, the vegetation is capable of filtering nutrients, sediments, and pollutants brought by agricultural, urban, and industrial run-off. Utilizing the nutrients but allowing the sediments and pollutants to slowly settle out, thick mats of ground cover and wide nets of roots can cleanse the water. When, however, land upstream has been environmentally mishandled, unleashing, during periods of heavy rain, prohibitive amounts of flood water, the wetlands are unable to regulate the overflow. The velocity and weight of unchecked, rushing flood water erodes the land, uprooting and killing plants; the unusually large amounts of alluvial sediment deposited upon the soil by unassailable volumes of water block sunlight and prevent photosynthesis. When flood water can’t be managed, the wetlands begin to inch away from self-preservation, their contribution to life on earth diminishing with each reckless environmental transgression. Missouri’s flood plain wetlands deliver a tumult of well-adapted, hardy, and prosperous plant life, speaking to evolutionary energy and eccentricities that have earned its individuals a remarkable degree of success on land often appearing desultorily degraded and muddy with despair, as well as, in some instances, earning them honorable placement in our pharmacopeia as remedies for many human ailments. Almost half our state’s total plant species are associated with wetlands. Rich in wildflowers alone, some with common names as evocative as Blue Bottle Gentian, Queen-of-the-Prairie, Yellow Stargrass, Paintbrush, Shooting Star, Lizardtail, Water Pepper, Pickerelweed, and Copper Iris, the wetlands are not only visually stimulating but are busily sound scored by the disparate, compelling notes of droning insects, croaking frogs, singing birds, and waterfowl quacking and honking. Covering a total of 643,000 wildly alive acres, Missouri flood plain wetlands represent, from riverbanks to uplands, nature’s strength, vibrancy, purpose, and intelligent design. Onto this scene gallops the energetic and resilient Bugleweed, presenting itself, much like other members of the family of mint from which it descends, with great vigor and prolificacy having the singular ability to survive in even the most degraded parts of the wetlands. This rainy day, we search our flood plain wetlands for this wildflower, botanically named Lycopus virginicus. Locating the tall, rangy plant, almost indistinguishable in the misty gloom, we realize, upon close inspection, its striking markings. From its slender, three-foot-tall, square-shaped stem, pairs of oppositely arranged dark green, burgundy, or deep purple leaves fan out gracefully, with serrated edge, to three inches in length. Likened to the image of a wolf’s paw, it is from the leaves the plant acquires its botanical name: lykos (wolf) + pous (paw) = Lycopus. Further, and almost imperceptibly in the gray of the day, tiny whorls of white flowers hug tight the plant’s stem where the leaf pairs branch. Shaped like little trumpets (or bugles), it is from these flowers the plant’s fruit is born and its common name derives. Running along riverbanks, leaning heavily in marshes and swamps, ringing the ponds and lakes, casting great swaths of itself over the prairies and meadowlands, established in dampened ditches and thickets, and finding purchase even at the base of gravelly slopes of cliff bluffs, with speed and alacrity, Bugleweed briskly and robustly grows across all of the Missouri flood plains. Its swift reproduction results from its energy-saving method of propagation. Rather than generate seed, a host plant puts out extensive runners (stems) that stretch horizontally across the land. Dotted with nodes that yield roots and vertical branches, the runners create a network of new Bugleweed plants that remain connected to the mother plant until they establish themselves through photosynthesis and begin putting out runners of their own. In short order, Bugleweed weaves itself into the whole of the tapestry of the wetlands, making it a formidable competitor for ground space. Resting at the base of the front of the neck is a butterfly-shaped hormone gland called the thyroid. Just beneath the Adam’s apple, with its “wings” wrapped one around each side of the windpipe, the thyroid sits prepared to release hormones T3 (triiodothyronine) and T4 (thyroxine). The goal of these hormones is to direct the pace at which the body’s cells work. In other words, they govern the speed of metabolism. In the brain, attentive to numerous metabolic signals, the hypothalamus gland will, when the body’s levels of T3 and T4 become insufficient to meet metabolic demands, issue thyroid releasing hormone, which activates the pituitary gland to secrete thyroid stimulating hormone, that in turn, informs the thyroid gland to deliver more T3 and T4. Once the delivery of these hormones meets the body’s needs, the hypothalamus stops issuance of thyroid releasing hormone, the chain reaction is halted, and metabolic homeostasis is preserved through the elegance of a finely tuned feedback loop. Healthy regulation by thyroid hormones allows metabolic processes to move at the right pace: the slowing down or increase of heart rate; the raising or lowering of body temperature; the timing of food’s movement through the digestive system; the quickness with which the body burns calories; and the activity level of muscles, reproductive tissue, and the peripheral and central nervous systems. Masterfully juggling breathing, body thermodynamics, digestion, weight, energy expenditure, muscle strength and control, menstrual cycles and attempts at pregnancy, nerve function, cognition, mood, and sleep, the thyroid balances us, matching function to goal. In Graves’ disease, a condition of autoimmunity has developed. The immune system produces antibodies that seek out the thyroid stimulating it to release thyroid hormones, irrespective of the body’s need for them. Levels of T3 and T4 rise to excess, forcing metabolism into a hyper state and creating a condition of hyperthyroidism. Shortness of breath, high blood pressure, intolerance of heat, moist skin, excessive sweating, persistent hunger, increased frequency of bowel movements, weight loss, fatigue, muscle weakness, menstrual imbalance, difficulty ovulating, hand tremors, memory loss, nervousness, irritability, anxiety, depression, and insomnia are symptomatic of an overactive thyroid. The heart, particularly, is affected by the hyperthyroidism of Graves’ disease. Driven hard by an overstimulated thyroid, the heart begins to outpace itself, becoming acutely alert, overly sensitive, agitated, distracted, overtaxed, and exhausted. Running on empty, the heart, in this hyper vigilant state, begins to dysregulate in the form of tachycardia, palpitation, and dysrhythmia. What better herb to catch up with a racing heart than the spirited Bugleweed? Onto this scene of cardiac stampede it gallops, running after the speeding heart, reining it in, and turning it back toward healthy homeostasis. Having already an affinity for the heart, the herb’s most direct indication for use becomes the heart displaying a “want of energy with quickened velocity”. Bugleweed’s ability to help restore the heart in Graves’ disease hyperthyroidism results from its sedative action as well as from its ability to block the effects of thyroid stimulating hormone on the thyroid’s receptors; to inhibit conversion of T4 to T3 (the more active thyroid hormone); and its ability to obstruct the effects of Graves’ disease antibodies. The Eclectic physicians found Bugleweed’s ability to sedate to be “most pronounced and most frequently indicated where the vascular action is tumultuous, the velocity of the pulse rapid, with evident want of cardiac power. It controls excessive vascular excitement, general irritability, and diminishes exalted organic action. It is best adapted to irritability and irregularity of the heart.” Historical acknowledgement of Bugleweed’s benefits for an overextended, exhausted, and erratic heart led naturally to its use in cases of hyperthyroidism. Today, preliminary studies have yielded up those constituents in the herb that are involved in helping relieve the thyroid of undue and improper stimulation and consequent overproduction of T3. Able to wrest the heart from the grip of hyper vigilance, Bugleweed not only helps discourage some of the symptoms of hyperthyroidism but has found its way into general formulas for heart health. Herbs that combine well with Bugleweed in a condition of hyperthyroidism include Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis, which is not only a calming herb for the heart but has been found to have thyroid blocking benefit) and Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca, which is specific to cardiac anxiety in the form of tachycardia, palpitation, dysrhythmia, and high blood pressure). Should you put on a pair of boots and begin to slog your way through the Missouri flood plain wetlands to find this herb, you won’t have far to look. And if the day is sunny and warm, several small creatures will cross your path as you descend upon one of its wild groupings, for feeding on the Bugleweed will be aphids, grasshoppers, katydids, and caterpillars of the hermit sphinx moth, along with the tiny flies of the genus Neolasioptera developing inside galls on the stems and leaves. After the same nectar, beetles will be climbing toward the flowers where many kinds of bees, wasps, and flies swarm in the comfort of the afternoon. Bugleweed’s place in the flood plain wetlands rests assured. Sending its progeny running in all directions, it becomes an ever-widening feast for those dependent upon it as a source of food, as well as becomes an expansive tract of vegetation holding great areas of soil tight against erosion. On this sunny, warm day, if you observe just long enough, one of Bugleweed’s rarer pollinators may light gently upon the flowers. Don’t take a breath, don’t move, and the butterfly may linger with you. Dosing Suggestions: Believed best taken in liquid extract form. The German Commission E suggests a dose of 1 to 2 ml ( ~ 1 to 3 dropperfuls) three times per day. If combining Bugleweed with Lemon Balm and Motherwort, herbalist Hein Zylstra suggests adding Nettle to the combination and creating a liquid extract of equal parts to be taken in a 5 ml (1-tsp) dose three times per day. Safety Considerations:

For mild hyperthyroidism. Avoid use with moderate to severe hyperthyroidism. Avoid use with herbs Ashwagandha and Bladderwrack. Avoid use if taking hyperthyroid medication; have hypothyroidism or any other endocrine disorders; are using contraceptives or fertility drugs; are pregnant or lactating. Should not be taken in high amounts. Should not be stopped suddenly creating a rebound effect that increases thyroid stimulating hormone and hyperthyroid symptoms. Appropriately, if under medical supervision and using any prescription medicine, please discuss possibility of the use of Bugleweed, as well as any other herbs you wish to use in tandem with it, with your physician(s). Sources available upon request.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMaria and Ingrid are Co Owners of STL Herbs and Aromatics. They have been working in the field of Herbal and Aromatic Medicine for over twenty years. This blog is intended to inform and empower people to begin utilizing plant medicine for personal health and well being. Archives

December 2023

The products and statements made about specific products on this web site have not been evaluated by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent disease. All information provided on this web site or any information contained on or in any product label or packaging is for informational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for advice from your physician or other health care professional. You should not use the information on this web site for diagnosis or treatment of any health problem. Always consult with a healthcare professional before starting any new vitamins, supplements, diet, or exercise program, before taking any medication, or if you have or suspect you might have a health problem. Any testimonials on this web site are based on individual results and do not constitute a guarantee that you will achieve the same results.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed